Naomi Kawanishi Reis is a transcultural visual artist who looks for ephemeral moments of beauty and magic in everyday life. Using simple materials of paper, fabric, blades, and brushes, her work is rooted in folk traditions of craftmaking found in home workshops around the world. Born in Shiga, Japan, Reis has also worked as a copyeditor and translator from Japanese into English for more than two decades. Whether working with language or material, she is fascinated with the mystery of translation—the amorphous liminal space of in-between.

She has exhibited at Morgan Lehman Gallery (New York, NY), Praise Shadows (Brookline, MA), @KCUA (Kyoto, Japan), Tiger Strikes Asteroid New York (Brooklyn, NY), Transmitter (Brooklyn, NY), Youkobo Art Space (Tokyo, Japan), Mixed Greens (New York, NY), and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, among others. In 2018 she received a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, and in 2015 was a New York Foundation of the Arts Finalist in Painting. Reis received an MFA from the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania, and a BA in Transcultural Identity from Hamilton College. She lives in Brooklyn, NY — ancestral, unceded Lenape land — and whenever possible, her hometown of Kyoto, Japan.

Notes:

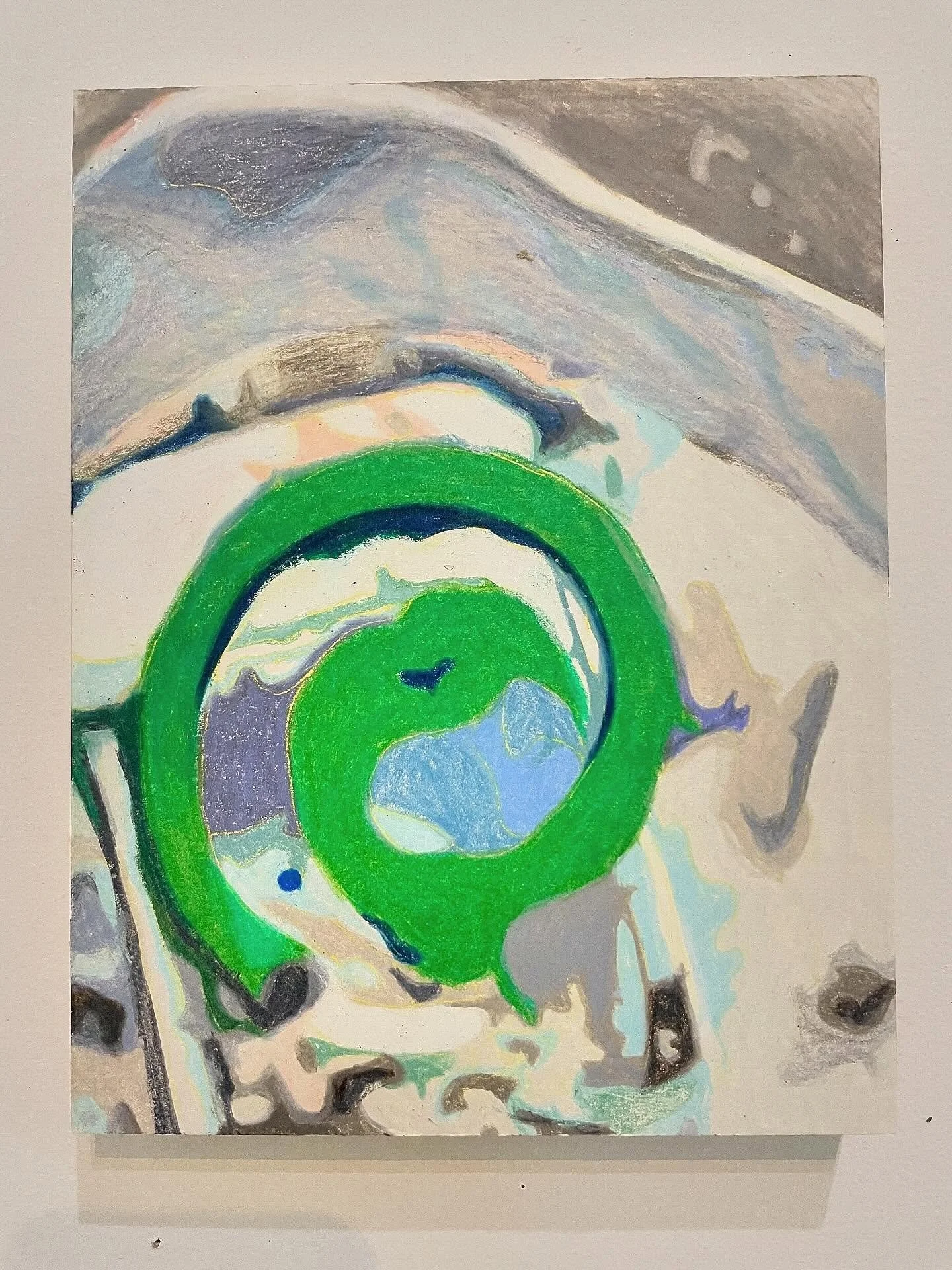

The humble materials I work with —paper, paint, brushes, blades—are a tactile reminder of the history of manual labor, and the many hands that pass knowledge down through generations. We touch paper every day, from money to junk mail, books, and in sacred ceremonies. Paper was once considered the most advanced technology of its time.

After two decades living in New York, I rediscovered washi's soft yet durable qualities—traditionally made from mulberry or gampi fiber, it can withstand being saturated with washes of pigment, dried, drawn upon and cut up. It can flex, fold and layer. It was made by craftspeople in their home workshops across Japan; it tells a story; it likes to be touched; it feels like home.

Each piece I make begins with a photograph: an artifact from the real world, a stand-in for what “is”—light and shadow captured by a mechanical lens. After applying digital filters to manipulate color and draw out interesting shapes, I translate the resulting imagery using self-taught methods, the illusion of space emerging slowly over a period of time. By leaving evidence of the labor that created it, I want to infuse that which may be too subtle or quiet to be seen with an aura of presence. Collage is a language for the disenfranchised to imagine new worlds which include them; re-pulping celebrates the decorative, the feminine, metaphors for the overlooked: the marginalized, the introverted. It celebrates the poetry of everyday life.

Musings:

- I’m interested in women’s labor, women’s creativity, labor of the hand. (I'm also thinking about male/household manual labor: my mother's father, who was an old-school blacksmith who made scythes and knives; his older brother, who was a farmer; my mother's family who dyed cloth for kimonos; my dad's dad's family who emigrated from Sweden to the States in the late 1800s to till stony fields in Massachusetts.) Honoring manual labor, retroactively backwards through the generations to times when the labor of our mothers and grandmothers and beyond - were seen as a household commodity, a basic resource entitled to the patriarch of the house, like air and water, and just as seamless and invisible. This extends not just to her manual labor, but to rights over her body, her ability to reproduce, take abuse, be like the silent and equanimous receiver of forces coming into the home from the outside world and absorbing, healing, turning external energies into the safe space needed to create a healthy home. What is the value of childless women (aka breaking the lineage of the patriarchal line) within the context of this world?

- By making labor-intensive collages that are larger than life, I want to foreground the feminine, the domestic - what's considered decorative - punch it up and give it power, allow it to take up space, allow space to be exuberant and wild

- Distilling ephemeral moments, imbuing them with more attention through the accumulation of hours of labor, over time (days/weeks/months)

- Still life comes from an innate and universal human desire to distill and capture a moment, starting with what’s right in front of us, in our intimate, domestic spaces. The things we live with that are familiar to us, are extensions of our body— phenomenological space. In that way still life has always been an intimate snapshot of the life of the subject, a way of life at a moment in time, told through the objects we use. An attempt to ask life, aka time , to stop so we may see it, experience it, languish in it. Defying time also means defying death (annihilation, erasure), at least for a moment. This look at death through something that was once living is at the heart of ikebana: taking seasonal ephemera from nature, and asking it to stay still for a moment through arrangement. An aestheticization of the idea of death, a reminder that like these life forms, we, too, will someday no longer be here in the physical plane

Installation View , "Strange Light" at Morgan Lehman Gallery, 2024